History of Freediving and Apnea

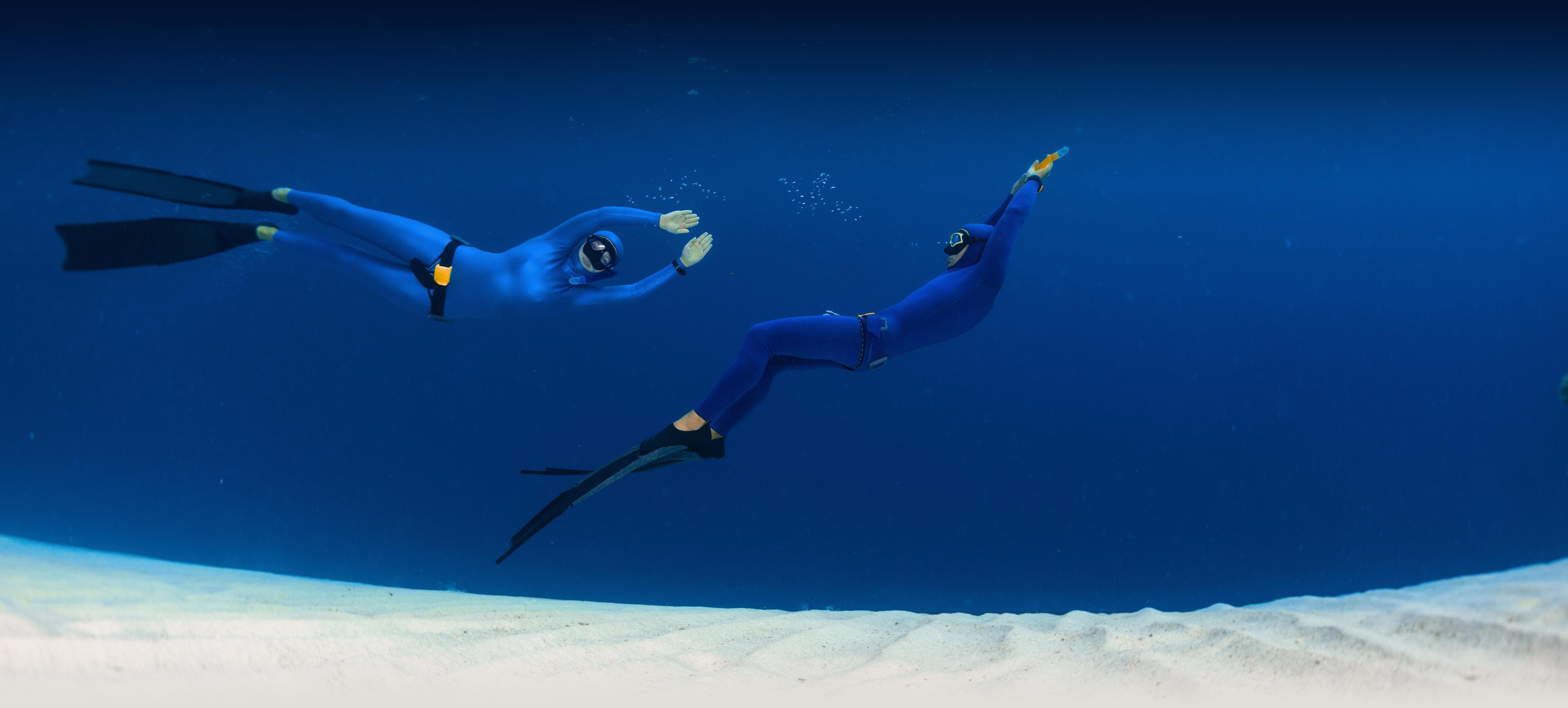

Freediving is as ancient an activity as humanity itself. More than any other sport, freediving is based on old subconscious reflexes written in the Homo Sapiens genome.

The word Apnea derives from the Greek word a-pnoia literally meaning “without breathing”. The origin of this word doesn’t have connection to water, but in modern athletic terminology “Apnea” has become a synonym for freediving, i.e. diving on one breath of air, without using equipment that would make it possible to breathe underwater.

From Origin to Modern Times: The Myths

Since 1960, a divisive scientific theory labelled the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis, published by the late Sir Alister Hardy, has circled among scholars. From the 1930’s, the Oxfordian Hardy had suspected that humans had primate ancestors more aquatic than previously imagined. He based this on studies of human lack of fur being replaced by a layer of insulating sub skin fat, similar to that of marine mammals rather than modern apes. This theory indicates that swimming and diving was a key ingredient in the eon long development of the Homo family from before Out Of Africa to modern times.

The oldest archaeological evidence that would confirm human breath hold diving dates back to at least 5.400 B.C. A Scandinavian Stone Age culture called Ertebølle (in some sources: “Kjøkken-møddinger”) lived at the coasts of Denmark and Southern Sweden, and were believed to have been a culture of shellfish eating freedivers, as witnessed by large excavated kitchen mittens.

Similar and plentiful archaeological proof of diving has been found in the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations dating back to 4.500 and 3.200 years B.C. respectively. On the Mediterranean coast freediving was a regular practice during the classic ages, reported by plenty of myths and legends. One Hellenic myth tells about Glaucus, which could be labelled the first mythological freediver. He was named “The Green Mariner” and the myth recalls that he ate a magical herb, which gave him fins and a fish’s tale. A tale from the Greek-Persian wars tells of a Greek fisherman and his daughter Cyan who at night swam under water, cutting the anchor ropes of the Persian war ships. In another story, the antique Athenians cut the underwater wooden barriers of Syracuse.

The legendary philosopher Aristotle is the first to document the common problems associated with diving, e.g. nose bleeding and pain in the ears. Alexander the Great used divers and even a diving bell during his military campaigns. In the Roman Empire existed a war unit called “Urniatores” with such tasks as recovering lost anchors, removing underwater barricades and other specialized sub aquatic war tasks.

In Asia, across the Middle Eastern, Indian and Pacific Oceans, the desire for pearls and other aquatic goods fueled freediving activities for centuries. Most famous of these freediving traditions is that of the Amas. Today these Japanese and Korean female divers still use a diving technique that are at least 2000 years old. Women between 17 and 50 years of age use rocks to plunge to the bottom where they pick up shells and sea weeds, while diving naked 8 to 10 hours a day in water barely over 10 degrees Celsius.

1913: The Legend

In the summer of 1913, the Italian naval flag ship “La Regina Margherita” lost its anchor off the Greek island Karpathos. A reward was offered for its retrieval, which gave way for the strongest of freediving myths: 35 year old Chatzistathis (also: Stathis Chatzi, or Italian: Haggi Statti), one of the leading sponge divers from nearby Symi, stood only 1.70 meters tall and weighed 65 kilograms; he suffered from remarkable lung emphysema, smoked tobacco extensively, and was part deaf from a life of diving without proper equalization. However, on July 16, he salvaged the anchor from estimated 88 meters depth, freediving up to three minutes at a time. He was carried down by a heavy stone, this primitive ‘Skandalopetra’ diving technique being as old as the Greek civilization itself. His reward was a sum of 5 pounds Sterling and permission to use dynamite for fishing. The legend of Chatzistathis was considered vastly exaggerated until 2001, when the Italian Navy officially confirmed most previous reports.

1949: The Year Zero

In 1949, the Hungarian-born Italian fighter pilot and avid spear fisher Raimondo Bucher founded the modern sport of freediving by announcing that he would reach a depth of 30 meters on a breath hold. Using a large rock for ballast, Bucher completed the dive outside Naples, presenting a parchment in a cylinder to a surface supported diver. Bucher later confessed to have done it all for a lavish bet of 50.000 lire with the diver waiting at the target depth, fellow Italian Ennio Falco, which two years later broke Bucher’s record.

1950’s – 1960’s: The Masters

Bucher’s Italy became the nourishing site for early competitive freediving, seeing freedivers like Alberto Novelli and Brazilian Americo Santarelli surpassing the depths of Bucher and Falco. By 1962, one of the greatest freedivers of all time emerged on the scene, as Enzo Maiorca prompted the first major development of the then obscure sport of deep freediving, which he dominated for the next 25 years. Maiorca was the first to reach and breach the fateful 50 meters barrier in 1962, despite predictions from scientists that beyond 50 meters, the human lungs would collapse from the pressure. Maiorca kept increasing his depths virtually unchallenged, this until Frenchman Jacques Mayol was introduced in 1966. Born in Shanghai, China, Jacques Mayol revolutionized freediving with his use of Eastern yoga and meditation traditions, as opposed to the previous norm of heavy hyperventilation. Maiorca achieved a fantastic record career that included no less than seventeen world records. Mayol was not far behind with his eleven world records, while also being the first to breach 100 meters.

Also introduced at this time was what is possibly the most influential freediver to date. Despite mere three logged deep dives in the late 1960’s, American Robert “Bob” Croft revolutionized the science of freediving extensively. Having worked 22 years in the United States Navy, Croft was training submarine personnel at a 36 meter deep training tank in Connecticut, when fellow instructors urged him to test his limits. For the next 18 months, Croft’s achievements competed with the best of Enzo Maiorca and Jacques Mayol in Europe. Croft was the first to freedive beyond 70 meters, and his achievements were key in establishing most modern scientific conclusions about freediving, among them the mammalian diving reflex and the blood shift phenomenon. Bob Croft was also the first record breaker to use lung packing, the Glossopharyngeal Breathing Technique, in his last breath before his dives.

Croft retired early, but both Mayol, reaching 100 meters depth with his sled in 1976, and Maiorca continued deep diving well into their fifties, both having passed 100 meters by the 1980’s, and they subsequently found world fame with Luc Besson‘s 1988 motion picture The Big Blue. This beautiful, albeit heavily fictionalized depiction of Mayol and Maiorca’s 20 year long sportive rivalry, is still considered the best visual representation of the “Zen” of freediving. At this time, there were very few freedivers in the world; the 1943 invention of the aqualung had lead scuba diving to overrun freediving both professionally and leisurely, but the success of Besson’s movie brought a renewed global interest to the age-old activity.

1960’s – 1980’s: The New Amas

By the 1980’s, female freedivers had developed to a point, where they claimed a bigger place in the annals of apnea. Already in the mid 1960’s, women such as Giliana Treleani (Italy) and Evelyn Patterson (Great Britain) had gone beyond 30 meters depth. The discipline later known as Constant Weight Apnea was fashioned by women such as Italians Francesca Borra and Hedy Roessler long before taken on by fellow countryman Stefano Makula in 1978. But it wasn’t until two of Enzo Maiorca’s daughters Patrizia and Rossana Maiorca took up records in the late 1970’s, that female competitive freediving finally took off. Later, athletes like Italian Angela Bandini and in particular Cuban Deborah Andollo took female achievements deeper and deeper into the oceans. Bandini caused a sensation in 1989, when she reached 107 meters of depth with Jacques Mayol’s now classic freediving sled, hereby going two meters deeper than Mayol’s then world record, making her the deepest human being in history at the time.

1970’s – 1980’s: And Suddenly She Quit

In this period, competitive freediving was at a peculiar crossroad. From around 1960, the successful scuba organization CMAS (Conféderation Mondiale pour les Activitités Subaquatiques) had homologued the bulk of early freediving achievements. This continued until a combination of medical and safety concern led CMAS to suspend most of its freediving activities around 1970. This didn’t hinder record breakers, who still increased the depth levels of humanity, but now without unilateral standards, resulting in a couple of serious accidents up until 1990.

1980’s – 1990’s: New Kids on the Block

1990 – 2001: The Birth of AIDA

In 1990 Roland Specker, a freediver from the North East of France, met world-class freediver Claude Chapuis from Nice, and they decided to organize clinics so that others could also discover freediving. Specker and Chapuis also set out to create proper regulations for freediving world records, when in fact many records were being established without homogenous global rules. Specker and Chapuis sought out a number of European freedivers, aiming to unite them in an association to recognize records. On November 2nd 1992, Specker, Chapuis and a few others created the “Association Internationale pour le Développement de l’Apnée” (AIDA), with Specker being its first President. Several records were quickly recognized by AIDA, which were to become the reference for freediving.

The birth of AIDA launched a period of political volatility surrounding competitive freediving. By 1995 CMAS again started to recognize records in response to the AIDA initiative, defining their own separate set of regulations. Francisco Rodriguez, who had become a key figure in the development of No Limit Apnea and the broad media exposure of freediving, developed a long lasting opposition to AIDA. In 1997 he fathered the short-lived IAFD (International Organization of Free Divers), which monitored his later records. In protest to controversial decisions made by AIDA, by 1999 in Italy was formed the organization FREE (Freediving Regulations and Education Entity), also to regulate records. Most developing efforts kept shifting towards AIDA though, all while records kept increasing worldwide.

Through the early 1990’s, Claude Chapuis had organized small competitions between the freedivers attending the clinics held in Nice, and the thought of organizing a world championship quickly grew. The 1st AIDA World Championship was thus held in Nice in October 1996. It was a competition for national teams featuring Constant Weight and Static Apnea, with 35 participants each in teams of 5. The actual nationality of an athlete was not considered particular as the need for filling up teams competing for Germany, Belgium, Columbia, Spain, France and Italy rose. A team representing the United Nations consisting of left over freedivers from various countries was also ascribed. Modern competition freediving was born on that day and subject to improvement. On departure day, Claude Chapuis shook Umberto Pelizzari’s hand and said, “You won; now it’s up to you to organize the second World Championship”.

1997 was a year of transition and several freedivers created groups in their own countries. AIDA continued to certify records with 12 countries on the contact list, requiring each of these to create their own national AIDA association. The AIDA baton was by then largely held in France; Thierry Meunier and Laurent Trougnou initiated an early AIDA website to promote the development of freediving via the Internet, giving all freedivers the opportunity to stay in contact.

Umberto Pelizzari kept his word and hosted the 2nd AIDA World Championship in Sardinia in 1998. Now 28 countries attended and the event was praised as well organized. Jacques Mayol’s presence created an emotional atmosphere, and during the competition France and Italy went neck-to-neck, mimicking Mayol and Maiorca’s past rivalry, with Italy and Pelizzari himself claiming the gold.

By this time, many new competitive disciplines were suggested by record thirsting freedivers. Most were rejected, others were tested and found too light. Since around 1990, world best achievements in a pool training discipline later labelled Static Apnea was noted in the margin of the book of apnea. For a while AIDA kept distinctions between depth records set in sea and fresh water, and briefly between short and long pool records in the new discipline called Dynamic Apnea: Already in the 1900 Paris Olympic Games, “Under Water Swimming” had been tested but not repeated. Combining scores from both length and time achievement, Frenchman Charles de Vendeville swam 60 meters in little over a minute, and has so far been the only Olympic Freediving Champion. This makes Dynamic Apnea (in a mix with Static Apnea) the oldest form of competitive freediving.

By the mid 1990’s static and dynamic disciplines saw increased attention, with a major contributor being Frenchman Andy Le Sauce, whose ultimate limits in both Static and Dynamic went unchallenged for five years across the turn of the millennium.

In 1999 “AIDA” became “AIDA International” to keep up with the continued development. On September 21st Roland Specker handed over the AIDA presidency to Swiss Sébastien Nagel. Being AIDA’s responsible for records prior to taking the reins, the Lausannian Nagel became notorious for his logistic skills. In his presidency, AIDA and freediving saw an explosion in numbers of registered athletes and competitions, regulations development, and increased media coverage of freediving. Nagel also foresaw the forming of a large number of new national AIDA bodies, uniting these in the AIDA Assembly introduced in his time in office. The new president was surrounded by a group of international freedivers on an executive board counting Claude Chapuis, Frédéric Buyle (Belgium), Dieter Baumann (Austria), Karoline Meyer (Brazil) and Kirk Krack (Canada). The list of international contemporary freedivers grew with names such as Italians Gaspare Battaglia, Davide Carrera, and most notably Gianluca Genoni; this alongside Yoram Zekri (Belgium), Alejandro Ravelo (Cuba), Benjamin Franz (Germany), Jean-Michel Pradon, Michel Oliva, Loïc Leferme (France), Pierre Frolla (Monaco), Topi Lintukangas (Finland), David Lee (Great Britain) and Eric Fattah (Canada), as well as French women Nathalie Desréac, Audrey Mestre, Turkish Yasemin Dalkiliç, and the American wave Meghan Heaney-Grier, Annabel Edwards, Jessica Wilson and Tanya Streeter. By 2003, Streeter mirrored Angela Bandini’s 1989 feat by breaking the inter gender No Limit world record, reaching 160 meters depth.

By 1999 freedivers kept pushing the limits of breath hold diving. Umberto Pelizzari became the first to reach 150 meters in No Limit, and the first to reach 80 meters in Constant Weight. By now, Pelizzari had earned the respect of freedivers worldwide, considering him the best all round freediver of all time.

The big annual competition was the Red Sea Dive Off ’99 in El Gouna, Egypt, at the hands of local organizer Magda Abdou, amassing 23 nations. Following the first Red Sea Dive Off in 1998, an individual competition organized by Francisco Rodriguez and IAFD and won by later AIDA President Bill Strömberg, this second Dive Off included both an individual and a team event, comprising results in Constant Weight and Static. The individual event, won by respectively Claude Chapuis and Karoline Meyer, saught to test if freedivers were ready for individual events of an international scale. This event was plagued by a vast number of blackouts and the “samba” phenomenon (loss of motor control upon exit), while the team event saw almost none, being won by the Italian male team by one point margin to the French team.

In 2000 AIDA experimented with a new format, a World Cup. In an effort to minimize the number of blackouts and sambas, at the time a heavy point of critique by eg. CMAS, and based on the experience from El Gouna, AIDA kept the team format. The three competitions in Montreux, Switzerland, in Nice, France and in Soignies, Belgium saw limited success, and some expressed desire to see more individual events worldwide.

2001: A Legend’s Last Hurrah

In 2001, with the support of Club Med, the young Spaniard Olivier Herrera organized the 3rd AIDA Team World Championship in Ibiza. The Italian men lead by Umberto Pelizzari came first, France second, and Sweden third. For the women, in order, the Canadians with Mandy-Rae Cruickshank took gold, the Americans with Tanya Streeter silver, and the Italians with Silvia Dal Bon bronze. Herbert Nitsch (Austria), later to be not only one of the most dominant figures of freediving, but likely the most complete freediver ever, reached 86 meters in Constant Weight, a new world record. Shortly after this championship, Pelizzari announced his athletic retirement following one last world record attempt, where he completed a Variable Weight dive to 131 meters depth.

2002: On to Hawaii

In 2002, AIDA USA representative Glennon Gingo organized the major international competition Pacific Cup – Jacques Mayol Memorial International Competition, in Kona, Hawaii, originally intended to be part of the World Cup. World record holders were finally regularly participating in competitions; athletes like Martin Štěpánek (Czech Republic), Carlos Coste (Venezuela), Guillaume Néry, Stéphane Mifsud (France), Stig Åvall Severinsen (Denmark), Bill Strömberg (Sweden) and many others lit the scene. Bob Croft’s presence at this competition made the event something to remember for all participants. Now 27 teams competed, and on the men’s podium at the end were found the Swedish team including a female athlete, Charlotta Ericson, taking the silver medal just behind the Venezuelan team with Carlos Coste. AIDA had finally succeeded at uniting the best competitors in the world.

Tragedy

In October 2002, the worst possible incident struck freediving. Audrey Mestre, wife of Francisco “Pipin” Rodriguez and by now one of all time’s best female freedivers, lost her life during an official world record attempt off the coast of the Dominican Republic. She had set out to break the No Limit world record across both genders, and while trying to complete a 171 meter deep dive, her diving sled malfunctioned and she failed to reach the surface in time. The dive had been organized by IAFD, and the onsite security measures were heavily criticized in an emotional debate over the Internet following the accident. Most public flag went to Rodriguez, who consequently quit the freediving scene, his credibility exhausted. Few months prior to this tragedy, German Benjamin Franz had suffered a severe case of decompression sickness while training No Limit in the Red Sea, and had since been confined to a wheel chair. The now highly active freediving community instigated a complete re-evaluation of the deep diving safety measures, and as one consequence, AIDA introduced the mandatory use of a safety lanyard and back up lifting systems in deep diving disciplines.

2003: The Show Must Go On

2003 was somewhat a year of coincidental hiatus in AIDA in terms of a big international event, but did see the introduction of Constant Weight without Fins. This discipline had originally been developed and promoted by FREE, seeing its first proponents in Yasemin Dalkiliç, Topi Lintukangas and David Lee, before being inaugurated by AIDA. CMAS was not entirely done with freediving either and this year The Old Lady launched a new initiative: The Jump Blue. The format was to freedive as long as possible in open sea along a rectangular course at a depth of 15 meters. This competition form was criticized by some, and took off with limited success.

2004: Emerging Regularity

The 4th AIDA Team World Championship took place in Vancouver, Canada in 2004. This time Germany was the one to glitter as they took the golden cup, being the first non-Mediterranean country to do so, with second and third being the United Kingdom and Canada. In the women’s competition Canada was best followed by USA and Germany. Some criticized the otherwise well-organized competition for being held in Canada, the cold Northern waters blamed for only 10 countries participating. One other important event that year was the BIOS Open competition, seeing the first freediver, Carlos Coste, officially past 100 meters depth in Constant Weight.

2005: Individuality

More and more, local clubs were organizing individual pool competitions, and in 2005, Sébastien Nagel organized the 1st AIDA Individual World Championships in Renens, Switzerland. The competition disciplines where Static Apnea, Dynamic Apnea with Fins, and Dynamic Apnea without Fins. The best athletes in the world surpassed 200 meters in Dynamic and 8 minutes in Static, with 3 new world records set by new female master Natalia Molchanova from Russia. A new surface protocol had been introduced in response to controversy surrounding past ruling on the samba phenomenon. A mere week later the 2nd AIDA Individual World Championship was organized in Nice covering the Constant Weight discipline, and again Molchanova claimed the gold.

In 2005 Sébastien Nagel stepped back from being the president of AIDA International after 6 years, and colorful and experienced freediver Bill Strömberg from Sweden took his place. He took over an AIDA that by now administered competitions all over the world, being organized almost on a weekly basis, and with the community steadily growing. A new website was launched, now including an official set of world ranking lists, which had existed a few seasons prior in an Internet bootleg version. Contemporary freedivers now included Russian Alexey Molchanov, young son of Natalia Molchanova, Ryuzo Shinomiya (Japan), Peter Pedersen (Denmark), Juraj Karpiš (Slovakia), Tom Sietas (Germany), Patrick Musimu (Belgium) and Johanna Nordblad (Finland). Tom Sietas became a dominating figure across all pool disciplines and has to date claimed the highest number of AIDA world records with nineteen; one 2004 static world record of 8’58” stood unsurpassed for nearly two years. He is credited as the first to use neck weights in Dynamic Apnea, revolutionizing these events.

Patrick Musimu caused some controversy, when he announced that he would attempt to breach 200 meters in No Limit, but outside the supervision of any diving federation. On one last training attempt in June, Musimu reached 209 meters depth with his sled and successfully returned to the surface. Minutes after surfacing, he suffered symptoms of decompression sickness and received hyperbaric treatment, which cancelled the public attempt scheduled few days later.

A major media event in 2005 was the IWC World Static Apnea Contest, held in Monaco in July and organized by Pierre Frolla. This was the biggest freediving event yet to date, in terms of exposure and cash price. It was broadcasted live via the Internet, and had 500 seated spectators, including Prince Albert of Monaco, and saw Stéphane Mifsud take 1st prize.

By now, CMAS had further developed their freediving formats, launching their own separate annual world championships. The Jump Blue format was still its only open water activity, now along with a dynamic apnea format virtually identical to that of AIDA’s. Still, the bulk of the world freedivers sought out AIDA venues, the CMAS events regarded as a side opportunity.

2006: A Sphere Too Far

In 2006, freediving became subject to a peculiar and litigious media event. American street magician and endurance artist David Blaine, as part of a stunt in which he submerged himself in a water filled sphere for seven full days, also aimed to break Tom Sietas’ then Static world record of 8’58” as a big finale to his show; even though it wouldn’t be approved as an official world record by AIDA. In front of millions of TV viewers and thousands of spectators in New York, on May 1st Blaine held his breath, while simultaneously trying to escape from handcuffs. Onsite safety divers and co-organizers of the event Kirk Krack, Mandy-Rae Cruickshank and Martin Stepanek were forced to intervene, when the otherwise talented breath holder Blaine blacked out 7 minutes and 8 seconds into his dive.

By December 2006 the 5th AIDA Team World Championship was held in Hurghada, Egypt, seeing Denmark take gold medal in the men’s ranks, and a legendary Russian team claiming the women’s gold in a competition plagued by organizational problems.

2007: Dives for the Ages

In 2007, AIDA launched new guidelines for sled diving and by summer Herbert Nitsch, who had now risen to dominate virtually all freediving disciplines, set out to reclaim the No Limit record he had held twice before. He aimed to surpass Musimu’s unofficial, but widely acknowledged 209 meter dive in the increasingly dangerous discipline. During his four and a half minute long, now 214 meter deep dive, thus surpassing the 700 feet marker, the innovative Nitsch made use of deep-water breath hold decompression, ascending very slowly to avoid the dreaded “bends”. He surfaced unscathed and claimed the record in this the deepest form of freediving.

AIDA foresaw the 3rd Individual AIDA World Championships held in Maribor, Slovenia. This almost perfectly executed pool event saw the introduction of a new competition format, having A and B finals for the best 16 freedivers across elimination heats. Head to head with 7 other freedivers starting simultaneously, Stig Severinsen claimed two gold medals out of three possible in the finals, and Natalia Molchanova took a triple-gold clean sweep. So far, Molchanova had taken all available female gold medals at individual world championships, setting new world records every time and being unprecedented in dominance among the women.

This was to change late in 2007 at the 4th Individual AIDA World Championships held in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. At a recurring annual competition, The Triple Depth, held in nearby Dahab just two weeks short of the world championships, a new light shone forth on the world of freediving; completely unknown British freediver Sara Campbell broke three deep diving world records in the space of 48 hours. At the following world championships, she claimed the Constant Weight gold at the expense of Molchanova, who suffered a severe competition blackout and was disqualified. Meanwhile, Herbert Nitsch claimed both possible gold medals, including the Constant Weight without Fins category now part of the world championships.

On a flip side, in 2007 freediving was struck by two laps of tragedy; first long time active AIDA judge and instructor, popular Dimitris Vassilakis (Greece) drowned while spear fishing, and later the French No Limit master Loïc Leferme lost his life in a private training session with his sled outside Nice. The sled became entangled during ascent, and Leferme failed to reach the surface in time. By a bizarre twist of fate, Leferme on the day was training down to 171 meters, the exact same depth as the one that claimed the life of Audrey Mestre five years earlier.

2008: The Present Future

The 2008 6th AIDA Team World Championship returned the world-class freedivers to sunny Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt. The Russian female team was again triumphant with an unprecedented margin down to USA and Japan. In a close men’s competition, the French team took the gold with less than 10 points down to the Czech Republic with Finland as runners up.

As of 2008, AIDA has officiated 204 world records and presented 156 world championship medals. Resent seasons have revealed talented freedivers like William Winram (Canada), Dave Mullins, Ant Williams, William Trubridge (New Zealand), and also Elisabeth Kristoffersen (Norway), Annelie Pompe (Sweden), Jarmila Slovenčíková (Czech republic) and Karla Fabrio (Croatia), with more arriving just beyond the horizon. Freedivers today have held their breath for more than 10 minutes, swam further than 250 meters in length and gone beyond 200 meters in depth, all on a single breath of air. As records continue to be broken, there seem to be no end to the aquatic potential of Homo Sapiens. As competitive freediving continues to evolve, it is AIDA that oversees this evolution, combining freediving efforts from a total of 65 countries worldwide today.

Text – Christian Engelbrecht, January 2009